In Found, Book 3 in the Folk series, the hero and heroine take refuge in a Rocky Mountain cabin during a magically nasty blizzard. But this isn’t just any cabin: it’s a Tenth Mountain Division Hut. I chose their lodging on purpose because, frankly, I think the Tenth Mountain huts are neat.

In Found, Book 3 in the Folk series, the hero and heroine take refuge in a Rocky Mountain cabin during a magically nasty blizzard. But this isn’t just any cabin: it’s a Tenth Mountain Division Hut. I chose their lodging on purpose because, frankly, I think the Tenth Mountain huts are neat.

The Tenth Mountain Division has a definite place in Colorado’s heart. The unit was formed just prior to World War II when the head of the US Ski Patrol argued that the US Army needed special capabilities for fighting in mountain terrain. The members of the division had to apply for entry and they had to demonstrate athletic ability and some familiarity with mountain conditions. When it came time to train for mountain warfare, the army chose one of the toughest terrains in the US—a remote valley outside Leadville, Colorado. Camp Hale had an elevation of 9200 feet and the recruits endured some punishing conditions, particularly in the winter. Fortunately, the training paid off when the division played a critical role in alpine battles.

But the Tenth Mountain Division played an equally critical role in Colorado history. Members of the division who trained in the Colorado mountains came back after the war to found the modern Colorado ski industry. Tenth Mountain veterans founded the Aspen ski resort, and others played major roles in resorts at Breckenridge and Steamboat Springs. They also modernized the Colorado Ski Patrol and helped popularize skiing as a sport.

So what are these Tenth Mountain Huts? They’re a system of thirty-four backcountry huts for hikers, Nordic skiers, and snowshoers that can only be reached on foot. It’s possible to hike from hut to hut for a multi-night trek, assuming you’re an experienced backpacker—it’s not for beginning hikers. The area where the huts are located is close to the original location of Camp Hale, and the first hut was built by Tenth Mountain veterans.

Bertie and Eva, the hero and heroine of Found, regard the hut as a welcome shelter, and I made things a little more comfortable for them. For example, they’re able to drive to the hut, or at least close to it, but in reality they’d have to hike in (which would be hard for Bertie since he’s been poisoned). I also gave them running water and electricity, which the huts don’t have. A friend drives up with canned food and coffee, but to get to a real hut you have to pack everything in, which usually means no cans. I was caught between the needs of the story and the facts, and the needs of the story won. My apologies to fact-checkers everywhere!

You can reserve Tenth Mountain Huts through their website, assuming you feel like a hike, but the huts are very popular so you may not get the dates you want or you may have to share a hut with other hikers (the bedrooms are dormitory style). Still, if you’re an outdoors type, you’ll get to enjoy some spectacular scenery in a unique location. And even though I’ll probably never make the hike to the huts, I still enjoy hearing about them. Like I said, I think they’re neat.

When you’re writing a series, book 2 is often easier than book 1. In book 1, you’re getting used to the place and its people. The process is full of interesting discoveries, but it’s also time consuming. You’re constantly asking yourself if you want to go there or if you want to go there. People appear and take shape, and sometimes you have to toss them out and try again. It’s sort of like coming to a new town for the first time and finding your way. In fact, it’s exactly like that.

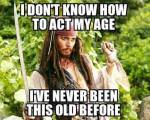

When you’re writing a series, book 2 is often easier than book 1. In book 1, you’re getting used to the place and its people. The process is full of interesting discoveries, but it’s also time consuming. You’re constantly asking yourself if you want to go there or if you want to go there. People appear and take shape, and sometimes you have to toss them out and try again. It’s sort of like coming to a new town for the first time and finding your way. In fact, it’s exactly like that. I’m illustrating this post with one of my favorite Facebook memes—the caption, in case you can’t see it, reads “I don’t know how to act my age. I’ve never been this old before.”

I’m illustrating this post with one of my favorite Facebook memes—the caption, in case you can’t see it, reads “I don’t know how to act my age. I’ve never been this old before.”