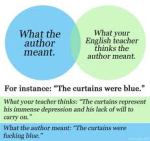

You see this meme repeatedly on Facebook—a Venn diagram showing the small intersection between what the author meant and what the English teacher thinks the author meant. Usually it’s posted by an author who’s convinced that English teachers are evil witches distorting an author’s true meaning. English teachers, say the authors, should just stick to grammar and leave literature alone.

You see this meme repeatedly on Facebook—a Venn diagram showing the small intersection between what the author meant and what the English teacher thinks the author meant. Usually it’s posted by an author who’s convinced that English teachers are evil witches distorting an author’s true meaning. English teachers, say the authors, should just stick to grammar and leave literature alone.

I’ve got a sort of unique perspective here since I’m an author and a retired English teacher. I’ve taught literature and I’ve taught grammar, and I’ve enjoyed both. Moreover, I agree with the poet Donald Hall who once said that a lot of people go into teaching English because they love to read and want to talk about books (Hall thought that was a problem, but I’m not sure I agree). I’ve also encountered the same kind of hostility toward interpretation that you get in that meme.

But here’s the thing: the meme implies that there’s only one meaning in a book, and it’s the meaning put there by the author. On the other side of that idea is reading theory, which holds that the meaning of a book rests with the reader, and that it changes with each person who opens the book. As a teacher, author, and reader, I’d say the truth lies somewhere between those two poles. Reading isn’t anarchy—some readings clearly have more validity than others. But authors don’t always see what readers see, and a work that can only be understood one way can be tiresome to read.

But what about those totally weird interpretations English teachers come up with? That goes back to the whole multiple meanings idea. Like other readers, English teachers come to books with a particular point of view. Some English teachers like to look at history (e.g., what was going on in Shakespeare’s England when he wrote King Lear?). Some prefer cultural criticism (e.g., how does nineteenth century colonialism inform Joseph Conrad’s work?). Some are feminists or psychologists or close readers who delight in language. Their interpretations seem weird only if you assume that there’s only one way to read—a meaning the author built in originally.

I’ve occasionally had people claim that reading that arrives at an interpretation other than the author’s “ruins” a book. One of my husband’s relatives once accused me of spoiling Huck Finn by suggesting it was a lot more than a “simple children’s book.” A quick aside: Huck Finn includes child abuse and murder, along with some shocking violence. I wouldn’t suggest giving it to a child unless that child is beyond the age of nightmares.

As an English teacher, I felt honor bound to push my students into looking beyond their kneejerk reactions to a book. That doesn’t “ruin” the book. That makes it richer.

In reality, English teachers can be authors’ friends. They’re sort of “super-readers”: people who love books and language, and who want to pass that love on to others. When they press students to go beyond their initial impressions of a book, they’re pressing them to think about what they’re reading. To pay attention to features like characterization and language, along with plot. Students who come out of a good English teacher’s class are more likely to be people who love to read. They’re not our enemies, folks, they’re our allies.